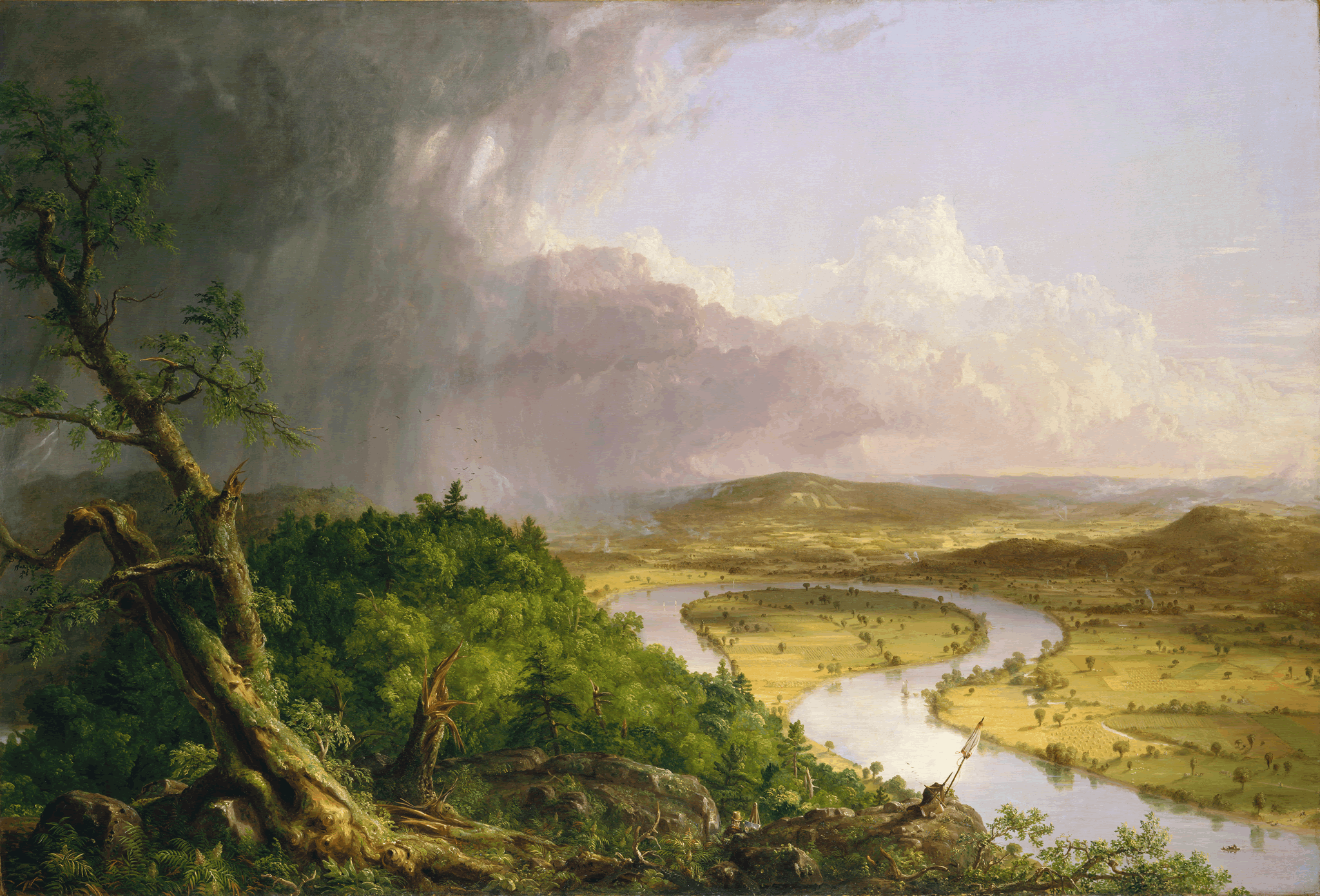

View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, After A Thunderstorm (The Oxbow)

About

Decode

Compare

Cole's Process

Cole's Words

Locate

About

Frustrated with his slow progress on The Course of Empire and worried about finances, Cole stopped work on the series to paint The Oxbow for the National Academy of Design annual exhibition of 1836. Writing to his patron Luman Reed, Cole explained his motivation for painting The Oxbow: "Fancy pictures seldom sell & they generally take more time than views so I have determined to paint one of the latter. I have already commenced a view from Mt. Holyoke. It is about the finest scene I have in my sketchbook & is well known. It will be novel & I think effective." 1 The site, where the Connecticut River forms a distinctive loop in its course, was another popular tourist attraction in the nineteenth century, complete with its own mountain house.

In The Oxbow, the self-portrait of the artist at work at his easel is a significant detail. In fact, Cole was one of the first American artists to execute oil sketches in the field. This detail shows Cole's apparent commitment to the empirical study of nature, emphasizing his method of painting en plein air. The artist seems to declare that the finished painting will be a "true" view of the site. Yet as much as Cole seemed to celebrate his activity of en plein air painting in The Oxbow, he downplayed its importance in 1835:

I think that a vivid picture of any object in the mind's eye is worth a hundred finished sketches made on the spot—which are never more than half true—for the glare of light destroys the true effect of colour & the tones of Nature are too refined to be obtained without repeated painting & glazings. And by my method I learn better what Nature is & painting ought to be—get the philosophy of Nature & Art—whereas a finished sketch may be done without obtaining either one or the other—and it is in great measure a mere mechanical operation. 2

In line with a well-established academic hierarchy, which exalted history painting over landscape views, Cole in fact regarded his ambitious "fancy pictures," such as the five-part Course of Empire, as his most important achievements. The artist once protested: "I do feel that I am not a mere leaf painter, that I have loftier conceptions than any mere combinations of inanimate & uninformed Nature. But I am out of place... there are few persons of real taste, & no opportunities for the artist of Genius to develope his powers; the utilitarian tide sets against fine Arts." 3

The Oxbow received mixed reviews at the exhibition, but to Cole's surprise it was sold for $500 to Charles N. Talbot, a wealthy New York entrepreneur. Despite its initial lukewarm reception, The Oxbowbecame one of Cole's most famous paintings and influenced numerous other Hudson River School artists in its panoramic format, broad sky, and extremely detailed foreground. 4 Part of its enduring appeal lies in how it powerfully conveys the artist's complicated ideas about the transformation of the American wilderness into a settled landscape.

Decode

Mouse over the detail to view its caption, click it to zoom in, and use the reset button on the lower right to zoom back out.

1. Thunderclouds roll out of the landscape to reveal a bright sky beyond. As in the contemporaneous Course of Empire, Cole visualizes the dramatic cycle of nature.

2. A blasted tree trunk represents the untamed wilderness.

3. The right side of the compositiondepicts the cultivated river valley inhabited by farmers.

4. The loop in the river (also known as Hockanum Bend) is nicknamed "The Oxbow" because its shape resembles the bowed wooden collar of a yoked ox.

5. This is a presumed self-portrait of Cole seated on the mountaintop, which proclaims the artist's affinity with untamed nature.

6. Cole signs his name on the artist's portfolio, and the stool is very similar to the one he actually used on his sketching trips, now in the collection of Cedar Grove. See also Cole's portable paint box. Interestingly, the protruding umbrella, used by Cole to shade himself while sketching, connects the two sides of the composition, which otherwise stand in dramatic opposition.

7. Some historians interpret the markings in the cleared mountain as Hebrew letters that spell "Noah" or, viewed from upside-down, "Shaddai" (the Old Testament word for "the Almighty"). This interpretation suggests that Cole recognized the potential beauty of the civilized landscape and used it to evoke a pre-industrial Holy Land. By carving a sacred name into the landscape, Cole also may have intended to identify God as the true artist of nature.

Compare

Basil Hall, View from Mount Holyoke, etching, 1829. Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections. View in Scrapbook

In comparison to a more straightforward view by Basil Hall, Cole's work endowed the prospect from Mount Holyoke with characteristic embellishments: the blasted tree trunk and dramatic thunderstorm, for example. In these transformations, we see the artist—like his umbrella—straddling the divide between empirical study and imaginative transformation of nature. 1

Process

Beginning in 1829 and continuing for many years, Cole's ideas for The Oxbow evolved. In the double-sheet Panoramic View, Cole adapted European landscape conventions to suit his American audience by stretching out the composition and elevating the viewpoint. Panoramas in Europe may have influenced Cole during his first trip abroad. By adapting panoramic painting techniques in his sketches, Cole could convey feelings of the sublime. European panoramas usually depicted architectural views and cityscapes, but Cole used the technique for American wilderness and pastoralscenes. The small preliminary oil painting, executed in the studio, is a more compact version of the outdoor sketch, allowing Cole to experiment with the color palette before moving on to the final canvas. 1 In this long, complex process, the artist transformed his view (a recognizable depiction of an actual scene) into an inventive veiled allegory about the confrontation of nature and culture in the American landscape.

Works

1. Thomas Cole, Panorama of the Oxbow on the Connecticut River as Seen from Mount Holyoke, graphite pencil on off-white wove paper, c.1833. Detroit Institute of Arts. Founders Society Purchase, William H. Murphy Fund, 39.566.66, 39.566.67. View in Virtual Gallery

2. Thomas Cole, Sketch for View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, After A Thunderstorm (The Oxbow), oil on composition board, c. 1836. Private Collection. View in Virtual Gallery

3. Thomas Cole, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, After A Thunderstorm (The Oxbow), oil on canvas, 1836, 51 ½ x 76 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1908, 8.228.

Words

Yet American scenes are not destitute of historical and legendary associations—the great struggle for freedom has sanctified many a spot, and many a mountain, stream, and rock has its legend, worthy of poet's pen or the painter's pencil. But American associations are not so much of the past as of the present and the future. Seated on a pleasant knoll, look down into the bosom of that secluded valley, begirt with wooded hills—through those enamelled meadows and wide waving fields of grain, a silver stream winds lingeringly along—here, seeking the green shade of trees—there, glancing in the sunshine: on its banks are rural dwellings shaded by elms and garlanded by flowers—from yonder dark mass of foliage the village spire beams like a star. You see no ruined tower to tell of outrage—no gorgeous temple to speak of ostentation; but freedom's offspring—peace, security, and happiness, dwell there, the spirits of the scene. On the margin of that gentle river the village girls may ramble unmolested—and the glad school-boy, with hook and line, pass his bright holiday—those neat dwellings, unpretending to magnificence, are the abodes of plenty, virtue, and refinement. And in looking over the yet uncultivated scene, the mind's eye may see far into futurity. Where the wolf roams, the plough shall glisten; on the gray crag shall rise temple and tower—mighty deeds shall be done in the now pathless wilderness; and poets yet unborn shall sanctify the soil. 1

Find it here.